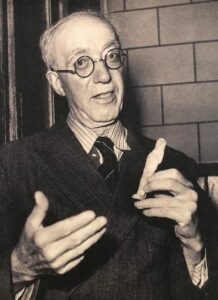

At the start of the last century, a group of people in the south of France, in the valley of the Ariège, wanted to carry out a similar vision or ideal. One of them was Antonin Gadal, a teacher and speleologist from Ussat-les-Bains. This vision became reality when this historian came in contact with the school of the modern Rosycross, in the persons of Catharose de Petri and Jan van Rijckenborgh.

Antonin Gadal knew the value of the spiritual history. He was looking forward to the moment when the Gnosis of the Cathars would once more find its way into the hearts of humanity. In the early1950s, he came into contact with the modern Rosycross, and the joy of Gadal, then 77 years old, knew no bounds. On the personal level, it was a mutual recognition.

Jan van Rijckenborgh and Catharose de Petri saw in him an older brother, who with a well-founded and inner knowledge could confirm their work. And Gadal recognized in his Dutch friends the leaders of a group who not only had kept the memory of the Gnostic idea, but at the same time were to their hearts’ content active with propelling it into life and workability: not only as a memory of the past, but as an adaptable force in the new times that were at the door.

And not only all this just for a small group of people in Haarlem, or for an even smaller group who had heard of the Cathars in Ussat, but for a group that had to be the start of a worldwide development. Gadal held many speeches, naturally about the so long-preserved wisdom and history of the Cathars and their roots, some of it rediscovered by him. At the same time, he pointed out that the basic values for spiritual life have remained the same throughout the centuries, similar to a river on the earth’s surface that at expected and also at unexpected moments floods and leaves the surrounding fields fertile.

With the portrayal of his tutor, Adolphe Garrigou, Antonin Gadal himself gave an example of a ‘keeper ’ of the type we wrote about in the foregoing. Recently, this inhabitant of Tarascon received recognition as a pioneer of the opening up of the caves in the valley of the Ariège and in general, as an important stimulator of the research into the history of the south of France. In a sympathetic and inspired article that Gadal wrote about Garrigou, we encounter all the characteristics that one admires so much in Gadal, also a similar struggle, which he lived through in the first half of the twentieth century. He sometimes called him ‘Papa Garrigou’ and later, more respectfully, ‘the Master ’ or also ‘the patriarch of the Sabarthez’.

Gadal told how as a youth he had become a reader and secretary for the then already ancient Garrigou, who had been born in the early days of the nineteenth century, on January 10, 1802. In his younger years, Gadal had tagged a long with Garrigou. Gadal had been a kind of private secretary to Garrigou, and he had to read to him because his eyesight had become weak. Garrigou is his turn found in Gadala spirit susceptible to the new ideas about history that he had gained over the almost one hundred years of his life, ideas partly based on an even older source, Napoléon Peyrat, a Protestant minister with a fond- ness for the native, national history of the Languedoc. With his History of the Albigenses, he wrote a fervent discourse against the Roman version of the history and showed with romantic and patriotic words a very different and older France: that of Aquitania, fighting for its independence.

From the outset, the young Antonin was immersed in this spirit: With the ancient Garrigou, his principal task was to listen and read curious texts from the unusual books that Garrigou possessed. He also had to write: He recorded what old Adolphe told him and whatever occurred to him. Adolphe Garrigou passed away in Tarascon at the age of 95.

The circumstances under which schoolteacher Gadal lived before the war were plainly poor. His salary was barely enough for a minimal sustenance of life. During the winter, the valley of the Arie’ ge was completely isolated, and nobody came there. From surviving letters of his extensive correspondence, it appears that often there was not even enough wood to burn throughout the winter. Then what did he envision as his task ? Why is he also called, like Garrigou before him, the protector of the Sabarthez?

He found himself placed before a number of problems. In the first place, like Eckhartshausen, Gadal lived in a predominantly Catholic region. How could he in such a case talk about the religion of free- dom?This was not without real danger. It becomes even more difficult, if you want to show secondly how systematically, thoroughly, and bloodily the perfect ones of Catharism, the pure ones of the Templars and the Rosicrucians, their pupils and their sympathisers were exterminated. Gadal accomplished this by exposing the Douad archives of the Inquisition, which were kept in Toulouse and Paris. For the Inquisition was very thorough and effective, not only in the hunting of heretics, but just as precise in recording all trials.

Thirdly, after all these centuries, he wanted to show what the real religion of the Church of the Cathars was, the Church of Love, of the Paraclete, not as described by opponents, but conveyed in a way that the beauty of the eternal longing radiated through it. On top of that, already before the war, he envisioned the idea of a spiritual Triple Alliance. He was aware that in the coming times, a triple bundling of spiritual force would take the realliberating work in hand. Before the Second World War, he thought that this concerned a cooperation between the Templars, the Rosicrucians, and the Cathars reverting, according to him, to a prior existing secret union of the three movements in the Middle Ages.

A fifth problem was that he might have been able to do all this and that it was important that these matters were rediscovered, but there also had to be a receptive ear; there had to be found a circle of people who could descry the line of the gnosis and at the same time could understand it.

In the years before the war, he had a great respect for the line of thinking of Rudolf Steiner, and he had even tried to make the gnosis known in France in that vein. However, in the end, this could not be the way of the new times, because Steiner thought an evolution was possible in the direction of the spiritual being, while according to Gadal an endura, a total yielding of the I-personality had to precede a total submerging in Christ, like the fidèles d’amour had also lived it.

He had influence on many other presently well-known persons. With each of them, he waited, and he hoped. This comes to light again in his correspondence of which a part is kept in the Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica in Amsterdam. We find among them names like Maurice Magre and Otto Rahn, René Niel and Deodat Roché. They had visited him more than once, and through him, they learned about the caves and their background. On top of this, he kept up a substantial correspondence with many thinkers in Europe who were interested in the Cathar past. Out of England, the interest came in the person of Walter Birks, who was sent by his esoteric order to the south of France with the mission to find the grail.

All his life, Antonin Gadal never deviated from the line of the gnosis, which stands diametrically opposite any ‘normal’ religion. This line and the history of Catharism as he perceived it ran along four points. Following this, he tried to further execute the task he experienced.

This gentle schoolteacher, Antonin Gadal, was at the same time an excellent speleologist. On his many excursions through the caves, he thus discovered the underground connection between the Cave of Lombrives and the Cave of Niaux, right through the mountain range. Presently, the latter cave, whose entrance lies at the opposite side as Lombrives, is famous for its pre-historic pictures, and it is very well possible that via this connection, people who looked for refuge in the caves exited at the other side.

It does not seem so strange anymore for us to meet Gadal, with his pure sense of symbolism and beauty, on March 16, 1944, at the foot of Montségur. After all, this was exactly 700 years after the murder of 205 Cathars, the last group of the true core of the Cathar religion, which were burnt on an immense pyre at the foot of Montségur. After a months-long siege and after Amiel Aicard had brought the famous ‘treasure of the Cathars’ to safety (according to the legend, he fled via the Pic de St. Barthélemy to Lombrives), the initiates, who had all received the consolamentum of the living, surrendered Montségur and gave themselves as ransom for the remaining population. Seven hundred years later, their spiritual relative Gadal would bring to fulfilment the prophecy that once was connected with this mass murder and with the religion that was so violently suppressed: ‘After 700 years, the laurel will once again bloom on the ash-heaps of the martyrs’.

Gadal loved his region; he loved the simple people of the area, and he had a lot of contact with them, as we are able to read in his own words. Conversely, the eldest among them still remember today how as children during the war, they saw Gadal busy sustaining the morale of Ussat, which was at the time totally isolated from the outside world, and how he organized everything to take care of the Polish refugees, who stayed there during those years. He even played the accordion for them!

But back to the special date of March16, 1944. In the still hesitating daybreak of a winter morning, seven men walked with a certain slowness towards the sacred place. Seven centuries, day after day, had passed since the first crack of dawn on that March 16, 1244, that gave light to the long line of Cathars destined for the pyre whose silhouette can still be guessed, a little lower, below the castle. Despite the difficult hour – it was after all in the middle of the war and very cold for the time of the year – these seven men, all of them Occitanians, gave clear proof of the immortality of their beloved Aquitanian native land and of its secrets. Among them were Maurice Magre, Antonin Gadal, and Alain Hubert-Bonnal. Their presence underscores the importance of the homage that was given

The grandmasters of the Spiritual School of the GoldenRosycross declared several times that in the new period, the Aquarius period, a mysteryschool would form, the Brotherhood of Christian Rosycross, which would be inspired by its founder. Several times, Jan van Rijckenborgh also said that many esoteric streams would be gathered in it. It would in time deliver proof that the labour that has taken place in the last two thousand years will then be combined in the work of the Young Gnostic Brotherhood, the Western mysteryschool.

And so the extraordinary life of Antonin Gadal led to a very delight- ful and a special crowning. After the many people who tried, in one way or another, to appropriate the Cathar inheritance, in Catharose the Petri and Jan van Rijckenborgh, Gadal finally saw the dawn of a new world activity: The first new branches had sprouted from the laurel, because their movement had already taught for many years the realization of the diminishing of the ‘I’.

For Gadal, it must literally have been that the prophecy had become reality! In this also for the Spiritual School eventful period of the1950s, he confirmed his new friends, his brother and sister, in their task at a number of ceremonial gatherings and officially connected them as far as this was possible with a long line of previous brotherhoods.

Antonin Gadal, as the last representative of one of the streams that flowed into the Rosycross, the preceding brotherhood, bestowed in the fall of 1955 in the Renova Temple the rank of grandmaster to Jan Leene (Jan van Rijckenborgh) and the title of archdeaconess to Henriette Stok-Huyser (Catharose de Petri). Presently, they are both referred to as ‘grandmasters’. Also, the Lectorium Rosicrucianum was connected by Gadal to the spiritual inheritance of the Cathars.

He spoke several times in the centres and the temples of the Rosycross, and in May1956, the construction of the conference centre Galaad started on a piece of land owned by Gadal. The meeting between the grandmasters of the Young Gnostic Brotherhood as a purely Christ-oriented community and Gadal was confirmed by the establishment of the Galaad monument on May 5,1957, in Ussat-les-Bains, which is dedicated to the Triple Union of the Light: Grail, Cathar, and Cross with Roses. After this, Gadal came to the Netherlands a few more times; one of these was for the consecration of the Noverosa temple in Doornspijk.

It is the tragedy of every worker in the service of the other one, that all his labour is not more than ‘one hammer-blow on the anvil of eter- nity’, as Van Rijckenborgh expressed it. Th is applied in 1938 to Zwier Willem Leene; this applied to himself, and this applied in1962 surely to Antonin Gadal. Honesty forces us to mention that in the later years, a certain melancholy beset his life, because he had expected that the work in the south of France would have taken wings to a greater degree and he had hoped that the Lectorium Rosicrucianum would concentrate its efforts more towards southern France.

However, the organisation was not yet strong enough. And its results were still lacking. In 1962, the last ‘initiate’ of the preceding periods, who had grown into a truly universal human being, passed away. The limited minds of the fortune-hunters and of the envious with whom he had to deal so often could not tie him anymore in anyway, for his liberated spirit was already since long looking over the valley of the Ariège and was and is connected with the ‘Way of the Stars’.

Source: ‘Gnosis Rays of light in Europe’ by Peter Huijs