Mysteries of God, Cosmos, Humanity, week 3

Reflection: consciously perceiving, thinking and acting

Many teachings that can be recognized as being from other religious, philosophical and spiritual traditions have been incorporated in the Hermetic philosophy, albeit in other formulations. Thus we find the tri-unity of body, soul and spirit and the distinction between four spheres or worlds not only in Hermeticism but also, for example, in the Indian wisdom, in Greek philosophy and in the Kabbalah, the Jewish Gnostic tradition.

How is it possible that there are so many parallels between the inner teachings of authentic traditions? Certain philosophers in ancient times and also in the Renaissance assumed that a primordial wisdom had been revealed in the east in the distant past, one that gradually came to the west through human travels until it reached the Greek philosopher Plato. They believed that it really only degenerated after the revelation of primordial wisdom and that we need to return to the primordial source of all wisdom in order to be able to partake of truth again.

This view, known as Platonic Orientalism, apparently assumes a limited three-dimensional consciousness because it is based on time-spatial thinking. From the perspective of a five-dimensional consciousness, however, it is clear that the structures of people’s inner experiences have a universal character, and are therefore not exclusively dependent on time, space and culture. Then it is understandable that teachings of different traditions are very similar because they are derived from something that could be called a universal doctrine of wisdom, to which every person can open himself inwardly, thereby gaining access to it as a first-hand experience. That process is somewhat similar to downloading knowledge and information from a source that is invisible, but can be accessed online.

We find the idea of Platonic Orientalism, for example, in the works of the priest Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499), founder of the Platonic Academy in Florence and translator of the Corpus Hermeticum; and one of his students, Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494), best known for his ‘Oration on the Dignity of Man’.

According to Marsilio Ficino, the original sublime wisdom can be traced back to the Persian prophet Zarathustra. The humanist Pico della Mirandola, diligently studying the Kabbalah, regarded Moses as the source of primeval wisdom. Both thinkers saw the Hermetic scriptures as a second mportant revelation alongside the Jewish-Christian Bible. The aforementioned Renaissance philosophers are often presented together with the Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno (1548-1600) as the great hermeticists of the Renaissance. However, research by Professor Wouter Hanegraaff at the University of Amsterdam shows that this is not justified, because those authors have not understood the Corpus Hermeticum as well as the Italian Lodovico Lazzarelli (1447-1500), who until recently has been put aside in history as an insignificant hermeticist.

This view is not correct, because the small Latin masterpiece ‘Crater Hermetis’, that Lazzarelli wrote in about 1493, and which was published five years after his death, shows that Lazzarelli had a much deeper understanding of the Corpus Hermeticum than all his contemporaries, and that his vision can be called downright innovative. Professor Hanegraaff therefore sees Lazzarelli as the most important hermeticist of the Renaissance. It is known that in the last part of his life Lazzarelli lived like a saint, entirely in accordance with hermetic and Christian teachings.

Progressive development

Lazzarelli does not consider Zarathustra or Moses as the primal source of wisdom, but Hermes Trismegistus. An essential difference between his vision and the opinion of his contemporaries is that Lazzarelli does not start with the notion of a regressive development in which everything has become increasingly worse, but from a progressive development in which, with the passage of time, humanity can increasingly and more powerfully reveal itself. Another distinction is that Lazzarelli does not see Hermeticism and Christianity as two completely different revelations, but as manifestations of one revelation, which continues unceasingly.

Lazzarelli points out great similarities between Hermetism and Christianity. As far as we know, Lodovico Lazzarelli is the first to equate Pymander, the indwelling spirit, with Christ, who becomes active in the person who has realized the inner rebirth. In Lazzarelli’s vision, progressive human development begins with Hermes Trismegistus, an archaic initiate-sage to whom Christ speaks under the name Pymander. His revelation was not yet perfect because most people could not yet understand it. According to Lazzarelli, we are only able to understand the inner rebirth after the incarnation of Christ in the man Jesus; then the Christ spirit can become active in every person who walks the right path to that end.

Lazzarelli loved literature, and in his younger years he dreamed of becoming a famous poet. To bring that goal closer, in 1473 he became a member of the Academy of Rome, where he trained as a humanist. In 1481 Lazzarelli met a preacher, Giovanni da Corregio, who had an immense impact on him, and he followed him as his master. As a result, he became a spiritual seeker, discontinued his training as a humanist and completely abandoned his ambition to become a celebrated poet of name and fame.

In 1482 he wrote a beautiful manuscript for his teacher containing all the hermetic writings that were known in his time. In the preface he mentioned his master as ‘Giovanni Mercurio’. Lazzarelli indicated herewith that he saw his master Corregio as Hermes Trismegistus (Mercury is the Latin name for Hermes), as a person in whom the divine has been realized, and who teaches others who are open to it. A paragraph from that preface reads:

‘Dear teacher, dearly beloved father Giovanni Mercurio: I have become so absorbed in the study of the divine books of Hermes Trismegistus and also in the most holy words of Moses and the prophets, and most of all in those of Jesus Christ our Saviour, that all other writings, whether of ancients or of moderns have completely lost their appeal to me and make me sick to mystomach.’

This quote could indicate that Lazzarelli had profoundly experienced gnosis, and had therefore gone through a fundamental change within himself, in accordance with the following hermetic statement:

‘The Gnosis of The Good is both divine silence and the stilling of all the senses. He who has once found it can no longer pay attention to anything else. He who has once beheld it, will no longer see anything else, nor can he listen to anything else, and even his body participates in this immobility. Where all physical perceptions and stimuli have vanished from his consciousness, he remains in tranquillity’ (Corpus Hermeticum 12:13-14).

From a certain point on, the desire of Lodovico Lazzarelli was no longer focused primarily on the sensible world, whereas this was and still is the case with a large majority of people. Our thinking is also strongly based on sensory perception and nowadays also on the tidal wave of information from smartphones, tablets, laptops and other devices that confuse and distract us.

The senses and the mind

It is important, of course, that through our five wonderful senses of vision, hearing, touch, smell and taste we interact with our environment – that we consciously perceive and feel, and that we reflect on our sensations and experiences in order to learn certain laws and know how to make the right decisions and perform the right actions. This allows us to learn and grow as a personality in a way that the American learning psychologist and educator David Kolb portrays in his model of the learning cycle of experimenting, experiencing, reflecting and conceptualizing; and the four learning styles of doer, observer, thinker and operator (see image 5).

All kinds of research show that our senses have been developed to work together. This means, among other things, that we learn best if we stimulate multiple senses at the same time. Such an abundance of sensory stimuli reaches us in daily life that it is virtually impossible to process them all at the same time. In order to be able to control the flow of information, we have learned to concentrate on parts of it. Most people are strongly focused on the images around them. They are visually oriented. Someone who focuses primarily on sounds is auditory. People who mainly focus on their feelings are said to be kinesthetic.

The so-called visual, auditory and kinesthetic modalities are effective in every person and alternate with each other, yet most people appear to have a certain preference in this which is expressed, for example, in facial expressions, body language and language use. When a visually minded person is positive about something, he says for example: ‘that looks good’. Those who are auditory may say ‘that sounds good’, while someone who is kinesthetic expresses himself with the words ‘that feels good’.

Consciously observing, thinking, deciding and doing is not only necessary to be able to live our earthly life well, but also to learn to understand something on the basis of analogies of domains that transcend sensory reality, and the grand plan that drives everything. In chapter 2 of ‘Admonition of the Soul’, Hermes formulates the latter idea as follows:

‘Though this world is a complex of contraries, good and evil being intermingled in mutual conflict, yet at the same time it containssemblances or shadows of things higher en more real, whereby the soul is awakened, and urged to its attention on itself, and to attain knowledge of the truth.’

In spiritual traditions we often find references to visual images, such as the metamorphosis of a caterpillar into a butterfly, as a symbol for the process of renewal that can take place in man; or a tree as a symbol of a person who has become a living connection between earth and heaven and can therefore produce fruit; and the shining star as a symbol for the resurrection body or golden wedding garment. George Gurdjieff uses auditory symbols when he refers to the scale or octave of music when teaching the course of processes with the help of the Enneagram, to display something of the qualities that emanate from God and which can be experienced by humans.18 And Jacob Boehme in his book Aurora mentions the flavors sweet, bitter, sour and acidic to represent some of the qualities that come from God that can be experienced by man.

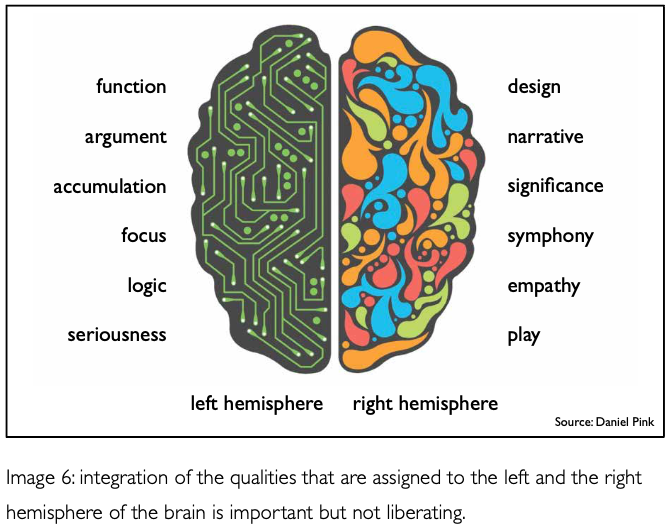

The attainment of the truth as intended by Hermes far exceeds what is known as common sense. The thrice great Hermes Trismegistus does not regard that as divine but as something similar to the senses, because it is also an aspect of the personality and is therefore bound to nature. This applies both to the rational, analytical way of thinking and to the creative and synthetic way of thinking. The first way of thinking is often linked to the left hemisphere of our brain and the second to the right hemisphere (see image 6).

Anatomically and physiologically it turns out to be incorrect, but that does not alter the fact that it may be useful to use the brain hemispheres as a metaphor for both ways of thinking.

The renewal of mankind through transfiguration can never exclusively come about through mere intellectual activity: not through the left hemisphere, not through the right hemisphere, and also not through the harmonious cooperation between the two. Integration of the qualities that are assigned to the left hemisphere and the right hemisphere is important, but in itself is not liberating in a gnostic sense. For the gnostic renewal process, it is essential to be touched in the heart. In order to be able to continuously experience that touch, it is necessary that the consciousness becomes calm and does not lose itself in fascination for the sensory world.There is of course room on the gnostic path for intellectual considerations – both analytical and synthetic – because the human mind is a wonderful and important instrument of the personality. Hermes says:

‘It is not, however, the mentality that reaches up to truth, but the soul that is connected to the spirit, having the power to forge ahead to the truth after it has first been guided to this path by the mentality. When it then ponders upon the entire All with a gaze that is all-embracing, finding how everything accords with what the insight-laden mentality has explained, its faith is raised to knowledge and it finds tranquillity in that fair knowledge of faith’. (Corpus Hermeticum 11:25)

This hermetic approach differs very much from a scientific method. Natural sciences are primarily based on physics, which deals with matter. The hermetic writings are mainly about metaphysics, that which is beyond the material and is related to the search for the purpose and meaning of existence. In hermetic philosophy, it is not primarily about defining truth in formulas or in words – because at best they are extremely limited reflections of the truth – but about coming into contact with, experiencing and living out of truth.

Paradigms

The human and world view presented by natural sciences is very extensive and detailed, but limited to what can be perceived with the senses or extensions thereof in the form of instruments. The view of man and the world within hermetics and other esoteric traditions is less complex, but includes much more because it is based on experiences that transcend sensory perceptions. That is why it is said that while gnostichermetic thinking is based on a completely different paradigm than natural scientific thinking, hermetic philosophy still accepts most of the conclusions of the natural sciences.

The concept of ‘paradigm’ was introduced by the American physicist and philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn (1922-1996) and refers to a system of beliefs, models and theories on the basis of which reality is perceived, analyzed and interpreted. A paradigm offers a high degree of certainty because it is based on a coherent set of beliefs that can be considered as assumptions that have been discussed extensively.

A self-contained belief offers less certainty than a paradigm, and an assumption even less. Paradigms, however, are a false certainty because history teaches us that old paradigms gradually give way to new paradigms due to advancing insight. The following quotes about paradigms can clarify things further.

- God’s Spirit moves through us and the world at a pace that can never be constricted by any one religious paradigm. Bono

- The symbolic language of the crucifixion is the death of the old paradigm; resurrection is a leap into a whole new way of thinking. Deepak Chopra

- A radical inner transformation and rise to a new level of consciousness might be the only real hope we have in the current global crisis brought on by the dominance of the Western mechanistic paradigm. Stanislav Grof

- Your paradigm is so intrinsic to your mental processes that you are hardly aware of its existence, until you try to communicate with someone with a different paradigm.

Donella Meadows - Since paradigms are often unconscious, you will not be able to face your own until they are broken. In that case, because it concerns the deepest level of certainty, you will also experience great instability. George Parker

Does all this mean that the paradigm of hermetic philosophy will give way to a broader and more precise paradigm? Absolutely! And that also applies to the paradigm of Christian salvation, which in the New Testament is represented as real,yet very elementary. Jesus says to his disciple: ‘I still have much to say to you, but you cannot bear it now. But when it comes, the spirit of truth, it will show you the way in all truth’. (John 16: 12-13)

The spirit of truth

Catharose de Petri writes in response to this Bible text in chapter 10 of ‘The Seal of Renewal’:

‘If we continue our work in absolute self-sacrifice with complete dedication, the spirit of truth shall manifest itself and speak to the world in even clearer language. A tremendous flow of truth, of revelations of coming events, will be liberated in the world. All countries and all peoples will be stirred by this new truth as by flood and alreadynow this can be witnessed everywhere. World and mankind are being,as it were, torn free from their limitations and their eyes will turn to matters of intercosmic concern, to the interrelation with the allmanifestation, in order that all may know that mankind must form a willing part of a glorious plan of salvation. […]

The truth will stir the all, now here, now there, as a mystery; one time as a whispering, another time as a stormwind. One moment it will speak of hardly expected and almost incomprehensibble things; the next moment it will testify in a clear manner. All will be stirred, small and great, the wise according this world and the simple. In this way an international goodwill towards the Gnosiswill be fostered.’

This grand prophecy might initially be considered strange and highly unlikely by people who are trapped in the paradigm that assumes the sensible world to be the only reality. In Hermeticism and other esoteric traditions, thoughts are seen as living creations that can be born and nourished, can increase and decrease in power and size and eventually die. Those who cannot recognize this idea as truth would do well to accept it as a working hypothesis and to then investigate in practice the extent to which this approach can be recognized as their truth.

Whereas most neuroscientists view thoughts solely as the effects of all kinds of electrical currents in the brain, the hermetic teachings consider thoughts as creations of a certain quality that enter into the consciousness of man such that he can become aware of them and that he himself can, in principle, decide what to do with them: let them pass, feed them, combine them with other thoughts and feelings, store them in memory and so on. Man’s thoughts and the way he deals with them determine who he is and what he does. Hermes very briefly describes the process by which man becomes what he thinks:

‘The human soul is manifested as follows: the consciousness manifests in the mind, the mind in the power of desire, the power of desire manifests in the vital fluid; the vital fluid spreads through the arteries, the veins and the blood; it sets the animal creature in motion and sustains it, as it were’. (Corpus Hermeticum 12-38)

On the gnostic path, the student gradually becomes more aware of his thoughts, feelings and acts of will, trying to direct his life in such a way that further inner development becomes possible; thus he ultimately contributes to the realization of the plan of God. He is not alone in that. If his intentions are pure, he receives the necessary insights and powers from the divine hierarchy at the right moments to enable him to go his path. If he joins forces with likeminded people who also walk the path of divinity, he will experience that this is based on a protective, beneficial and driving activity. He recognizes the truth in the following words that Hermes speaks to him:

‘Though this world is a complex of contraries, good and evil being intermingled in it in mutual conflict, yet at the same time it contains semblances or shadows of things higher and more real, whereby the soul is awakened, and urged to turn its attention on itself; and thus the soul is enabled to gain clear intelligence and to attain to knowledge of the truth.The soul descends into this world in order that it may make trial of things and learn to know them; but when it is here, it neglects its business of seeking and learning truth; it is drawn away to the pursuit of worldly goods and pleasures, and forgets the purpose for which it came down to earth.

Men use their senses amiss, and fail to attain to any true knowledge; but this world, rightly regarded, is a place for learning truth in. The visible forms of things which it presents to our senses are fleeting and perishable; but they are semblances or shadows of forms that are not apprehensible by sense, forms that are real and everlasting.

There is in the thought-world nothing of which copies are not to be seen among the things which are brought into being by the process of nature in the sense-world; and on the other hand, all things that are found in the sense-world are merely varying semblances or copies of things in the thought-world. The deceptive and fleeting pleasures of the sense-world suggest to us that we should turn from them to the true and unceasing pleasures of the thought-world; the frail, transitory, and perishable forms of the sense-world bid us turn from them to the stable and constant forms of the thoughtworld; the mutual repugnance and inconstancy of all things in the sense-world urges us to turn to the concord stability and constancy of all things in the thought-world.Therefore, O Soul, as long as you are in the physical world, seek not any pleasure (of sense), and suffer not yourself to be so occupied with any sensible thing as to be drawn away from learning to know, and representing to yourself in thought, and seeking out, those things which (it is your true function to) aim at and desire and pursue; that so you may be enabled to devote all your efforts to the one aim of getting knowledge’.

(Admonition of the Soul, Chapter 3)