Mysteries of Birth, Life and Death week 3

Reflection: fathoming cycles

You are called to freedom. Do you already experience that freedom? Or do you maybe feel yourself a slave in a modern world in which slavery has officially been abolished long ago? There are all kinds of forces in society that want you to believe that you are free, that you are entitled to a wonderful and abundant life and that you yourself determine what you shall manifest in your life and what not. At the same time, these forces are focused on sucking up the life energy of their victims so that they will remain unconscious slaves, and on maintaining their illusions so that they will not start looking for the meaning of life either in general or in their own life.

There once was a wise king in Jerusalem who wanted to live a wonderful life. He did all kinds of things that he thought would make him happy. So he had beautiful houses built and landscaped beautiful gardens and parks. This was rather a lot of work, but that did not matter. He collected valuables, ate the tastiest food, did not deny himself anything and had the best artists perform for him. This monarch indeed led a fantastic life, but there was one problem: it did not satisfy him. All the beautiful things in his life gave him some pleasure temporarily, but he experienced these pleasures as extremely fleeting – like everything in this world – and they gave him no lasting happiness. The king became painfully aware of his mortality and realised that he could not take his works with him when he died but had to leave them to those who came after him. His wealth was, as it were, thrown into their laps after his death, and it was very questionable whether they would handle it wisely. He therefore developed an aversion to life and went seriously looking for the why of everything.

The above story is a brief summary of the second chapter of the Bible book known as Ecclesiastes, also translated as Teacher or Preacher. It is a rather strange name for the author because he does not really preach but rather airs his doubts about everything in life. His Hebrew name is ‘Kohelet’ which literally translates as ‘predecessor’ or ‘collector’. He preceded us in accumulating everything that is desirable – possessions, knowledge and fame – and teaches us from his own experience that this life here is transitory, comparable to chasing the wind, and offers no benefit under the sun.

Later Jesus also teaches this to his disciples, but he immediately adds a hopeful assignment. In his famous Sermon on the Mount, for example, he says: ‘Lay not up for yourselves treasures upon the earth, where moth and rust consume, and where thieves break through and steal: but lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust doth consume, and where thieves do not break through nor steal: for where thy treasure is, there will thy heart be also’ (Matthew 6:19-21).

Universal character

You do not have to be a king to understand the thoughts and feelings of the king in this story. His experiences have a universal character. Every person is instinctively looking for meaning and as he grows up, the way he gives meaning to his life changes. Ecclesiastes describes himself as a wise king in Jerusalem who wholeheartedly pursued wisdom but is repeatedly disappointed by everything he experiences and gathers.

Chances are that this wisdom teacher was not a king at all – many think it could have been King Solomon – but rather presents himself as such to give his writings more authority. He succeeded because although his book was probably written in the third or fourth century BC and is contrary to many views within Judaism, it was still included in the Bible despite the hesitation of Israel’s scribes.

This Ecclesiastes might not have been the king of a nation, but he certainly was a ruler for his inner kingdom. Jerusalem is both a capital and a holy city. We may see this centre from which the country is governed as the symbol for the consciousness or the soul. Ecclesiastes is aware of his thoughts and feelings and moreover has the courage to ask himself difficult questions and draw utterly painful conclusions from them. He quite rightly states that there is nothing permanent in this world because everything changes constantly, and finally death is the end of everything and everyone. No one will deny this conclusion. Everything that appears will also disappear again. We are all familiar with the endless cycle of rising, shining and fading but do not always find it easy to accept it.

According to Ecclesiastes, it is a misconception to think that man is rewarded for his good deeds and punished for his evil ones. It makes no sense to do the right thing on earth with the purpose to reserve an attractive place in heaven or a nice next incarnation. That would only reinforce the ego-orientation, which now should instead be overcome. Ecclesiastes denies that man comes into an afterlife after his death. He sees that there is a lot of suffering among people and initially comes to the disturbing conclusion that it is actually better to be dead, and that not being born might be best. This denial of the value of life is a very bleak vision. Perhaps it is the didactic method of Preacher to urge readers to investigate what is right for them. Is life in no way worth the effort? Ecclesiastes clearly does not think so, because later in his argument he writes:

‘Go thy way, eat thy bread with joy, and drink thy wine with a merry heart; for God hath already accepted thy works. Let thy garments be always white; and let not thy head lack oil. Live joyfully with the wife whom thou lovest all the days of thy life of vanity, which he hath given thee under the sun, all thy days of vanity: for that is thy portion in life, and in thy labor wherein thou laborest under the sun. Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might; for there is no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom, in Sheol, whither thou goest’ (Ecclesiastes 9:7-10).

Is this advice not very superficial and hedonistic? Not at all! Everyone is fully able to do something with these recommendations. We are shown our own responsibility here and advised not to live according to rules drawn up by authorities. Ecclesiastes urges his readers to use their life as it is intended: to live it! Good listeners, pupils of the soul, may recognise a deeper, spiritual meaning in the counsels of Ecclesiastes. What he actually says is: Live with a happy heart, eat your bread, drink your wine, wear white clothes, have oil on your head, love your wife and toil under the sun; and this advice can also be understood spiritually, in a metaphorical sense.

Ruling the All

In Logion 2 of the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus says to his disciples: ‘Let him who seeks, not cease to search until he finds and if he finds he will be troubled, and if he is troubled, he will wonder, and he shall rule over the All.’ In this statement Jesus first appears to be in accordance with the statements of Ecclesiastes, but later in the text the two views differ greatly. Ecclesiastes speaks of the man who dies, enters the grave and finds it all ends there, while Jesus speaks about Man who will rule over the All. Can these two views be reconciled?

Yes, certainly! The big problem in our society is that in general we fail to distinguish between the various dimensions and levels of man. This problem affects not only the average person, but more especially the professionals who are intensively occupied with people and who should therefore know better, such as theologians, philosophers, psychologists, pedagogues, anthropologists and physicians. Almost all of them have been deluded by the materialistic and reductionist concept of humanity as derived from the natural sciences. This is an outdated paradigm that can certainly be valuable in a given context but is in essence extremely limited.

In the beginning of his argument, Ecclesiastes explains that everything that we perceive externally is extremely volatile. He refers to the four elements and mentions the coming and going of the generations on this world (earth), the coming and going of the sun (fire), the changes of the wind (air) and the constant flow of the rivers to the sea (water). He observes that this cycle is a returning one and that he finds them inexpressibly exhausting. He is a shrewd observer and notices that these cycles constantly need our attention but: ‘The eye is not satisfied with seeing nor the ear with hearing’.

Ecclesiastes makes it clear to us that a higher form of experience is not possible when we allow our consciousness to be determined exclusively by everything we perceive sensorially. We may on the one hand qualify a sunrise and a waterfall as ‘inexpressibly tiring’, while we may otherwise experience these natural phenomena from a different perspective as a proof of the divine, as a manifestation of the divine. Ecclesiastes invites people with fullness of experience to let go of their attachments to the world. In the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus formulates it as: ‘Let one who has found the world, and has become wealthy, renounce the world’ (The Gospel of Thomas, logion 110).

As humans we are subject to many cycles. In our body we possess the respiratory system, the circulatory system and the metabolism. The rhythm of day and night has an enormous influence on our functioning and the orbit of the moon around the earth also has a demonstrable influence on our lives. According to astrology there is a clear connection between the movement of celestial bodies such as stars and planets and their influence on our lives. This relationship is not a causal relationship but instead a relationship based on simultaneity, a synchronous connection, a correlation.

Intuitively moving in harmony

The key to the development of the inner being is the realisation that it is influenced by all kinds of cycles.13 It is certainly not necessary to know all those cycles, for example by drawing and interpreting horoscopes. This can even be counter-productive. What matters is that man learns to listen to the harmony of the spheres from a new perspective of life and intuitively move with the rhythms in the cosmos. That is why the author Antoine de Saint Exupéry in his small book ‘The Little Prince’ has the fox say: ‘It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.’

Ecclesiastes experiences that there is nothing new under the sun. This view is indeed true from a limited standpoint of only a few generations in a primitive agricultural society. From the perspective of the inner and outer history of the earth and humanity, however, it is a completely different picture, because the earth and humanity are continually monitored and influenced from the heavenly realms. Ecclesiastes probably knew this very well, and in his poetic text he probably wanted to point to something we call fullness of experience. Maybe in this way he wanted to encourage his readers not to focus exclusively on the sensory world, but to pay attention to what really matters and is imperishable.

Fortunately in our world of space and time there is progression in all kinds of areas. This progress certainly does not happen fully automatically. That would be contrary to the second law of thermodynamics, which states that every closed system strives for maximum entropy or disorder. The earth and humanity can develop because they continually receive energy from outside, specifically in the forms of consciousness, attention and light-power.

Well-known authors in the field of esotericism, such as Helena Blavatsky, Rudolf Steiner and Max Heindel, describe in their books how the creation of the cosmos and of man (cosmogenesis and anthropogenesis) takes place in seven cycles over seven spheres in the seven world eras. According to Heindel, the seven world eras are part of the so-called seventh cosmic domain and are designated by the names of planets from the solar system. Sequentially they are: the Saturn era, the Solar era, the Moon era, the Earth era in which we now live (which is divided into a Mars half and a Mercury half), the Jupiter era, the Venus era and the Vulcan era.

The danger of this approach is that these development are projected over time, while they really concern levels of consciousness which can in principle be experienced at any time and place. The three authors mentioned are influenced by the nineteenth century Darwinian belief that wrongly assumes progress as an automatic evolution. Currently we, as humanity, live in the fifth epoch of the Earth-era, the Aryan era. This period was preceded by the Polar period, the Hyperborean period, the Lemurian period and the Atlantean period. Rudolf Steiner distinguishes seven major cultural periods in this, our current Aryan period of 2160 years, the duration of one round of the precession of the equinox, which is the swirling movement of the earth’s axis.

Cultural innovation

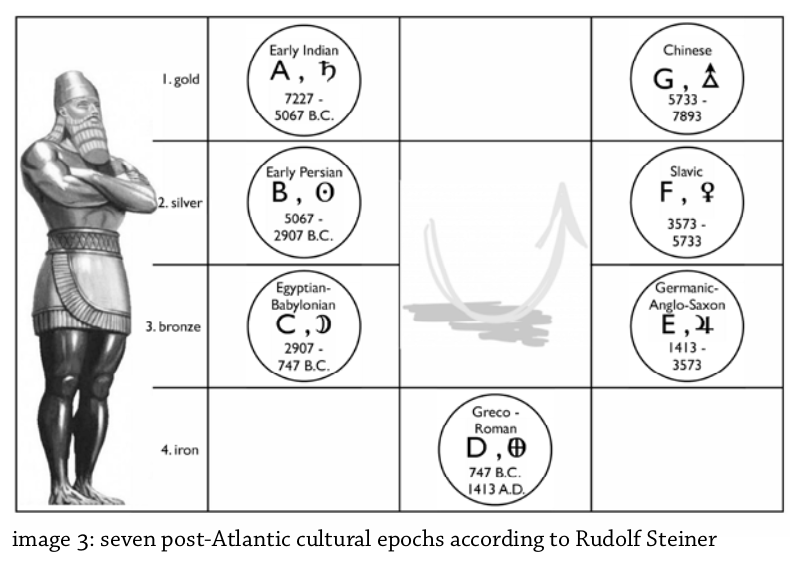

Steiner names these seven periods in the post-Atlantic period successively: the Primal Indian cultural period, the Primal Persian cultural period, the Egyptian-Babylonian cultural period, the Greco- Roman cultural period, the Germanic-Anglo-Saxon cultural period, the Slavic cultural period and the Chinese cultural period. These names indicate from which geographical areas the cultural renewal has been and will be shaped. Image 3 shows these seven cultural periods and the corresponding dates according to the structure of creation and re-creation pictured in image 1. Here, too, a connection can be made with the great image in the dream of King Nebuchadnezzar as it is explained by the Jewish prophet Daniel (Daniel 2) who makes it clear that everything is transitory in space and time. The four levels also correspond to the gold, the silver, and the bronze kings as well as the king of mixed metals in the subterranean temple in Goethe’s profound fairy tale of the green snake and the beautiful lily.

Image 3 shows that the Germanic-Anglo-Saxon cultural period in which we now live is a kind of mirror image of the Egyptian-Babylonian cultural period. In ancient Egypt there was a lot of attention on material things: large sculptures and buildings were realised and people revered dead bodies by embalming and mummifying them. Materialist science developed from about the fifteenth century onward in the Germanic-Anglo-Saxon cultural period. As humanity we are now faced with the task of spiritualising the materialistic development that began in ancient Egypt on the basis of the Christ impulse, which became active in the Greco-Roman cultural period at about the beginning of our era.

‘And what may be the purpose of my short life in this gigantic and unimaginable development process?’ you may wonder. No general answer can be given to such a question. But you can be sure that it is your task to become an essential cog in the great divine plan of development based on your unique qualities. This task extends far beyond your body and your personality since they are tied to space and time and cannot rule the All.

According to the cosmology of Max Heindel, your deepest essential being comes from the sixth cosmic domain. It is however connected to the seventh cosmic domain where it has undergone countless revolutions of the wheel. Your deepest being, that is the microcosm that you now inhabit with a dormant spirit spark as its core, is called to return to the sixth cosmic domain.

The being that you know and are is subject to decay and death. If your body dies and is then cremated, it is largely converted into water vapour and carbon dioxide. The water vapour becomes part of the water cycle and probably part of a cloud from which rain falls into a river that flows to the sea. The carbon dioxide is diluted in the air and taken up into the carbon cycle and possibly absorbed by some trees and converted by them, via photo synthesis, into vegetable material which is then deposited in the tree trunks.

The ashes of your body scattered over the earth may contribute to the growth of grasses and earthworms, forms of life that are absolutely essential for biological life as we know it on earth. You are part of the cycle of life on earth, as sung in Disney’s cartoon film The Lion King as follows: ‘It’s the Circle of Life, and it moves us all’. During our short existence we are constantly seeking until we have found our place in the cycle of life on earth. After you die, the elements of your disintegrated physical body are given back to a larger whole: ‘Dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return’ (Genesis 3:19). Something similar also applies to your psychic structure, your soul substance. In the course of your life you build up a personality soul from etheric, astral and mental substances that are then strongly expressed in your blood. That is why we speak of the blood soul. This blood soul is part of the nature we know, in which everything moves between polarities, and is therefore mortal.

Blood soul

When the body of a human being dies, the blood soul is dissolved into separate elements. Buddhism speaks of skandas in this context. When the deceased person was a conscious person with a strong individuality, then the blood soul can be transferred as inheritance to other people living on earth who have an affinity with it. And if the deceased was a pupil of the soul, a helping power based on the blood soul may be released. ‘Will there be anything left of me after my death?’, you might ask.

The answer to that question is determined by what you understand as yourself. If you identify yourself with your physical body, it is indeed completely finished with you when you die. In the natural sciences and in the medical world it is wrongly assumed that the consciousness will then have dissipated completely. That is why many researches and developments take place in these fields that are extremely questionable from a universal spiritual perspective.

Authentic spiritual traditions teach that after the death of the body, the consciousness can still be active for quite some time, and also that there is something else in the human being that is immortal. Lao Zu writes in verse 4 of his ‘Tao De Ching’: ‘The spirit of the valley never dies.’ In the book ‘Pymander’ or ‘Poimandres’ of the legendary Egyptian sage Hermes Trismegistus we read: ‘Of all creatures in nature, only man is twofold, namely mortal as to the body and immortal as to the soul.’

Ecclesiastes also recognises that there is a spirit in the human being who returns to God after the death of the body, after the silver cord –the connection between the etheric body and the consciousness– has been removed. ‘Man goeth to his everlasting home, and the mourners go about the streets: before the silver cord is loosed, or the golden bowl is broken, or the pitcher is broken at the fountain, or the wheel broken at the cistern, and the dust returneth to the earth as it was, and the spirit returneth unto God who gave it’ (Ecclesiastes 12:5-7).

Jesus refers to the immortal in man when he says, ‘The kingdom of God is within you’ (Luke 17:21). That inner kingdom, however, has fallen into disrepair. Isaiah speaks about a palace that has been abandoned (Isaiah 32:14). That is the microcosmic human system that should be a pure reflection of the macrocosm, but is no longer. It has fallen into ruin and needs to be rebuilt from the power emanating from the spirit-spark, so that man can rule his microcosmic All.

We conclude this analysis with a story from a book by Erich Kaniok.

‘A man went on a journey to consult a sage. When he arrived in the city of the sage and asked where he lived, they took him to a shabby hut on the outskirts of the city. In the cabin there was only a rickety bed and a table full of books that were being studied by an old man. The traveller looked around in amazement. ‘Where is the sage?’ he asked the old man. ‘I am the one you are looking for,’ said the old man. ‘Why are you so surprised?’ ‘I don’t understand it. You are a famous sage, with many students, they say. Your name is well-known throughout the country. It does not seem right to me that you should live in such a shabby cabin. You should live in a palace.’ ‘And where do you live?’ the old man asked. ‘I live on an estate, in a beautiful house with precious furniture.’ ‘And how do you make your living?’ The man explained that he was a businessman and travelled twice a year to a big city, where he bought raw materials that he then had brought to his place of residence to be sold to the local merchants. The sage listened attentively and asked the businessman where he stayed when he was in town. ‘I rent a room in a small inn,’ was the man’s answer. ‘And if someone saw you in that room, would he not say, ‘What are you doing here, prosperous businessman, in such a simple room?’ asked the sage. And then you would probably say, ’I’m only on the road for a short time, so I do not need more. Just visit me in my real house, then you will see something quite different.’ Well, my friend,

the same is true for me, continued the sage. I’m just on my way. The world is no more than a temporary stay. In my real house you would certainly see something completely different. Visit me in my spiritual home, then you will see that I am indeed living in a palace.’